On a snowy winter day in January 2024 at The Strong National Museum of Play, I read about the far-off land of Hyrule, inhabited by fiery dragons, rock-monster-people, and evil twin-sister witches. I pored over issues of Weekly Famitsu, the most popular Japanese gaming magazine, looking at their coverage of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. On page 89 of issue no. 507, I see the heading 謎の少年の正体が明らかにされる? (roughly: “Will the identity of the mysterious boy be revealed?”), with pictures of a character named Sheik. Of course, the game was released over 25 years ago, so I know the “boy” is none other than Princess Zelda herself in disguise. As a 5-year-old I was shocked when the mysterious and masculine Sheik revealed himself to be the extremely feminine Zelda near the end of the game. To this day, people are still debating what Sheik’s and Zelda’s true gender identity is.

Growing up, I played many Japanese video games that similarly messed with my expectations about gender, where I could tell something “weird” was going on but I didn’t have the words to describe it. When Cloud dressed up as a woman to enter Don Corneo’s mansion in Final Fantasy VII. When the lithe Raiden replaced the buff war hero Snake as the protagonist in Metal Gear Solid 2. Or when the “Detective Prince” Naoto Shirogane revealed she was a woman in Persona 4. Playing these games, I knew something was up, but I could never quite tell what it was. Well before I started working on my dissertation at The Strong, I experienced what Katsuhiko Suganuma calls the “contact moments” of queerness between Japan and the West, where cultural texts expose the asymmetrical political and social histories in understandings of gender, sexuality, and identity between the two nations.

I went to The Strong to engage in primary source research for my dissertation. I’m investigating how discourses about sexuality and gender identities circulate between the U.S. and Japan through the transnational flow of Japanese video games to U.S. audiences. I consider how the distinct but overlapping social, political, and linguistic histories of Japan and the U.S. impact how understandings of queerness arise within video games. In other words, I wanted to answer the question: Why did Sheik, Cloud, Raiden, and Naoto seem so weird, potentially queer, but intriguing to me as a kid?

Back at The Strong, I was looking for references to each of these characters in the Weekly Famitsu articles. I searched through dozens of issues, spanning from the late 1980s to the late 2000s, and I only had a week to get through them all. So I worked fast, with little time to translate or interpret any of the pictures I took. Although I started slow, I finished scanning the Weekly Famitsu issues by Day Five. On the last day, I tried to watch archived video game news coverage and developer conference talks. But I was drawn back to Famitsu, bothered by a common trend across the issues.

The scenes I found most interesting about these characters were completely passed over! The walkthrough of Final Fantasy VII quickly mentioned and then skipped over Cloud’s infiltration of Don Corneo’s mansion. Sheik and Naoto are referred to as men in multiple issues of Weekly Famitsu, with no conversation about their eventual gender reveals. And Raiden’s more feminine build and hairstyle are never contrasted with the buff masculinity of Snake.

As a magazine for a general audience including kids, these conversations may have been seen as inappropriate, as potential spoilers for the game, or as just something that didn’t need to be explained at all. Were Cloud’s feminine clothes seen as simply an afterthought of one scene in the game? Were Sheik and Naoto understood as just another iteration of the Japanese trope? Perhaps Raiden was meant to be just as masculine as Snake despite his contrasting stature.

I was in another contact moment, overwhelmed with trying to deduce all of these overlapping and converging understandings of gender, sexuality, social performance, and identity—all before I had even fully translated the photos I had taken!

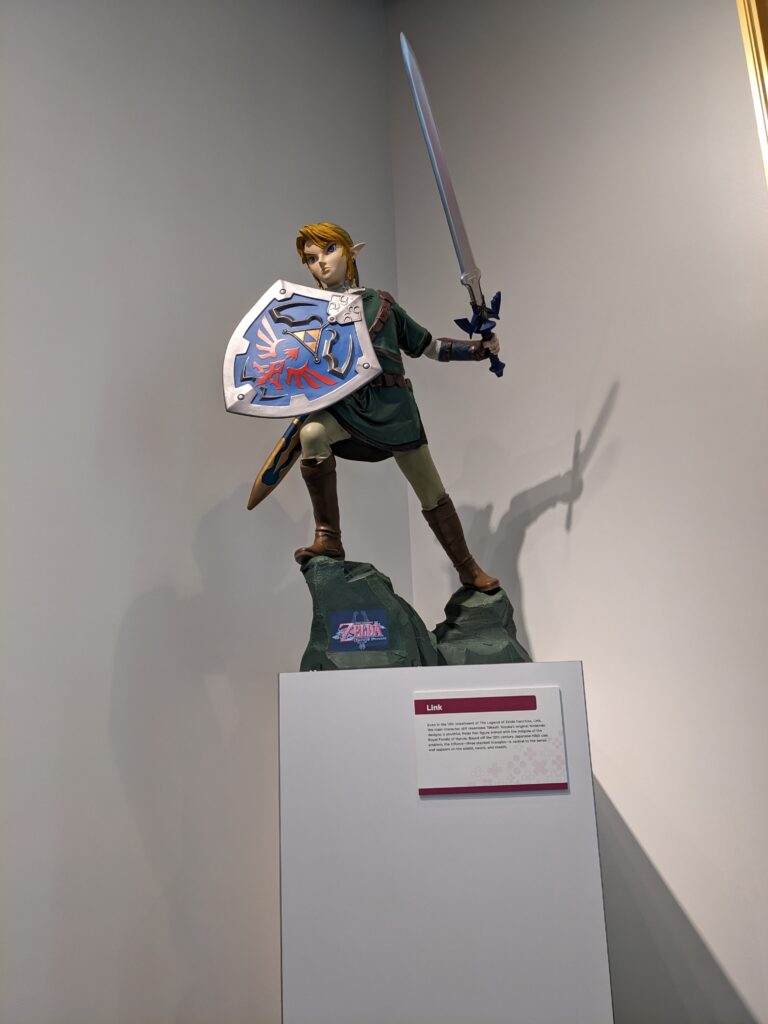

I needed a walk, to distance myself from the complexities of my research. I headed to the Level Up exhibit that I had saved especially for the last day. Unsure of where I was going, I stumbled across a large statue of Link, displayed prominently with his sword and shield. I hoped for a stroke of genius, that somehow the main character of my favorite game series since childhood would speak to me like a deity from above. But much like his in-game counterpart, Link said nothing.

But, following his gaze, I found my way over to the Level Up exhibit. I spent an hour or two just playing here—diving behind the boxes in the stealth room, rolling a yoga ball to guide a virtual rock down a hill, dancing to the beat. I was the only 29-year-old acting a fool in the exhibit, but it reminded me of how I felt playing Ocarina of Time all those years ago. The sense of discovery, of something new always waiting around the corner, and the wonder of immersing myself in a world that feels familiar but different.

I still haven’t figured out exactly how to describe the phenomenon I’m looking at. That’s what my dissertation is for! But I’ve learned a few things:

1. The concepts of gender, sexuality, and identity have distinct histories between Japan and the U.S., and those histories directly impact how players understand characters and narratives within video games.

2. As a dominant medium in the global marketplace, video games form a vital economic, political, and social connection between Japan and the U.S., two of the most dominant countries in the video games market from its inception.

3. Video games thus represent a significant contact moment between Japanese and U.S. developers and audiences, disturbing deeply held understandings of gender, sexuality, and other forms of identity.

4. These overlapping and contrasting understandings occur simultaneously with and inside of the ludic elements of video games, becoming the field where ideas about gender and sexuality are played out between Japan and the U.S.

5. I could stand to approach my research with the same playfulness and sense of wonder I bring to the games I play and love.

I want to thank Christopher Bensch, David Sleasman, Lindsey Barnick, Laura Boland, Deb Mohr, and the rest of the archive team for their help and support! And a special shout out to all the staff who continue to make The Strong Museum a welcoming and lively place!

By David Peter Kocik, 2024 Strong Research Fellow