ICHEG collects a vast variety of archival materials such as artwork, design documents, and interoffice communication that provide researchers with essential details about how game companies and designers conceived, thought about, created, and sold their games. Yet these sources rarely demonstrate the ways in which players shape the games that companies ultimately produce. Fortunately, ICHEG’s video game company collections also include invaluable materials that document how game companies used focus groups as market research tools to better understand consumers and improve their games. But what can historians learn from studying documentation of a video game company’s focus groups? An examination of focus group studies of Atari Inc.’s Asteroids (1979) and Her Interactive’s Nancy Drew: Secrets Can Kill (1998) reveals what kinds of questions game companies asked, how players responded to games still in development, and what broader industry and social concerns shaped the final product.

ICHEG collects a vast variety of archival materials such as artwork, design documents, and interoffice communication that provide researchers with essential details about how game companies and designers conceived, thought about, created, and sold their games. Yet these sources rarely demonstrate the ways in which players shape the games that companies ultimately produce. Fortunately, ICHEG’s video game company collections also include invaluable materials that document how game companies used focus groups as market research tools to better understand consumers and improve their games. But what can historians learn from studying documentation of a video game company’s focus groups? An examination of focus group studies of Atari Inc.’s Asteroids (1979) and Her Interactive’s Nancy Drew: Secrets Can Kill (1998) reveals what kinds of questions game companies asked, how players responded to games still in development, and what broader industry and social concerns shaped the final product.

Focus groups emerged more than 70 years ago, during World War II, when Columbia University sociologist Robert K. Merton used open-ended interviews with groups of soldiers to better understand how they responded to army training and morale films. Merton discovered that people were less reluctant to reveal their private thoughts when they felt comfortable and among people like themselves. Merton’s 1956 book The Focused Interview, which established interview techniques that focused on the respondent’s experience and personal context, laid the groundwork for the focus groups that market researchers used in the decades after World War II to help them improve product design and test advertising campaigns. By the 1970s, video game companies used focus groups to better understand how potential players felt about their products.

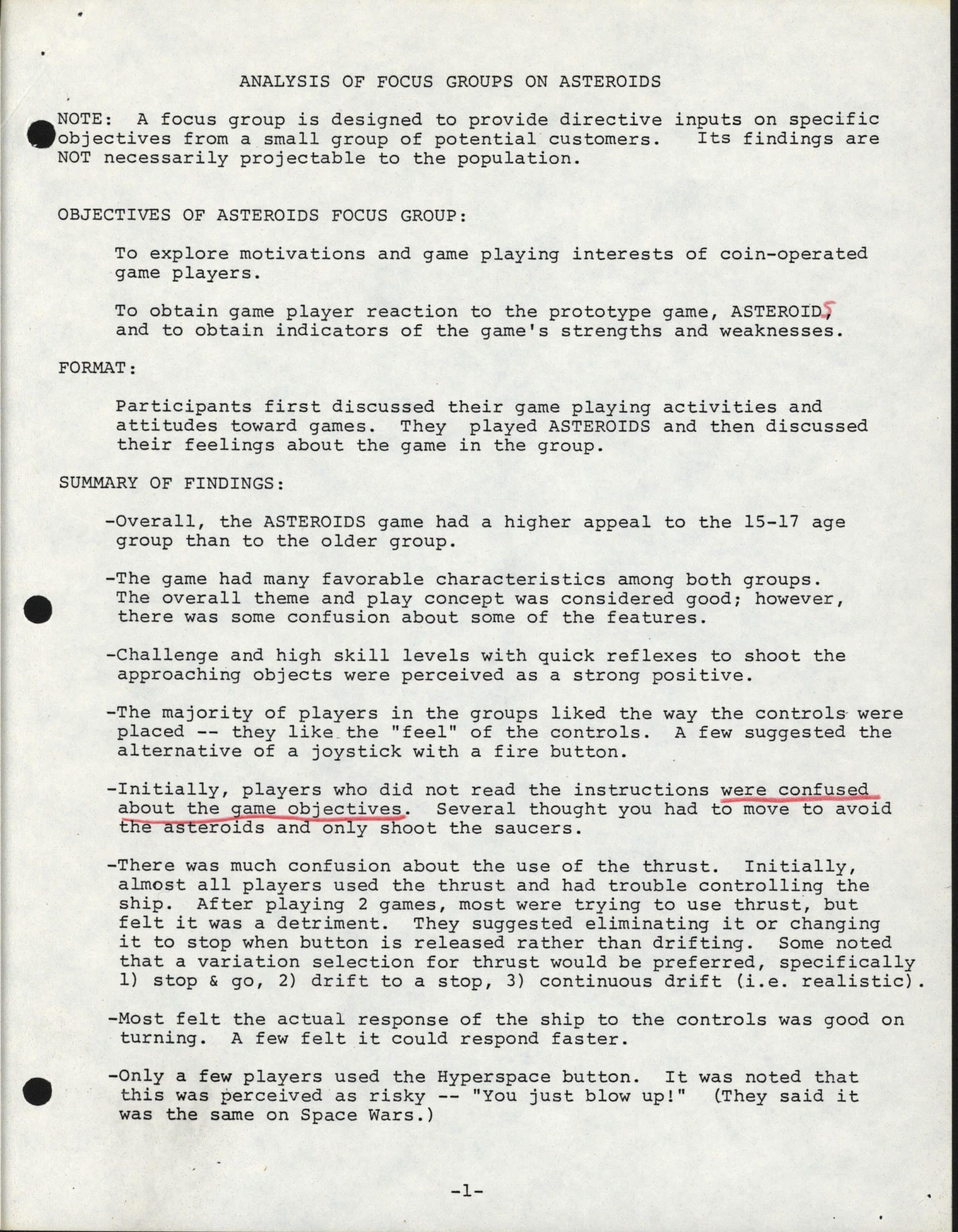

For video game pioneer Atari, Inc., focus group interviews provided the company with useful information about their customers and games. As documentation from June 1979 focus groups attests, the study aimed to “explore motivations and game playing interests of coin-operated game players” and to record player’s reactions to Atari’s Asteroids (1979), a shooting game that pitted a player-controlled spaceship against hurtling space rocks and the occasional flying saucer. Most players reacted favorably to the game citing “the continuous action as a ‘tension builder’.”

The comments and the design of the group also illustrate how enormous a shadow Taito’s immensely popular alien invasion shooter game Space Invaders (1978) cast over the video game industry. The success of Space Invaders spurred many other manufacturers to capitalize on the alien invasion shooter formula with similar games such as Midway’s Galaxian (1979) and Sega’s Space Attack (1979). Atari didn’t follow suit, but their focus groups suggest that Space Invaders remained on the minds of executives and players alike. As one player noted, unlike Space Invaders, players don’t “get a break” from constantly dodging and firing at rocks in Asteroids. Atari even created one focus group entirely out of 15 to 17-year-old “Space Invaders enthusiasts.” An Asteroids play test with another group at an arcade a few months later showed that many of the players surveyed compared and often preferred Space Invaders to Asteroids. Of course, those answers didn’t stop Asteroids from becoming Atari’s best-selling game of all time.

Focus groups almost always tell companies something about their products, but sometimes they shine a light on broader social concerns. For example, a 1997 focus group on Her Interactive’s Nancy Drew: Secrets Can Kill mystery adventure game addressed what players (all girls in this case) thought of the game’s proposed characters. Although some of the comments focused on practical elements such as whether it was appropriate for Daryl to be wearing a long-sleeve shirt in Florida, other comments demonstrated how much players cared about how game designers represented a character’s race, ethnicity, or gender. Notes on the focus group suggested that Connie “should be a feminine boy or masculine girl, and be attractive either way” and that she has an “androgynous [sic] quality that works.” Comments like these underscore the kinds of social concerns that some people bring to video game play as well as the kinds of choices that game designers have to grapple with when they create characters.

Focus groups almost always tell companies something about their products, but sometimes they shine a light on broader social concerns. For example, a 1997 focus group on Her Interactive’s Nancy Drew: Secrets Can Kill mystery adventure game addressed what players (all girls in this case) thought of the game’s proposed characters. Although some of the comments focused on practical elements such as whether it was appropriate for Daryl to be wearing a long-sleeve shirt in Florida, other comments demonstrated how much players cared about how game designers represented a character’s race, ethnicity, or gender. Notes on the focus group suggested that Connie “should be a feminine boy or masculine girl, and be attractive either way” and that she has an “androgynous [sic] quality that works.” Comments like these underscore the kinds of social concerns that some people bring to video game play as well as the kinds of choices that game designers have to grapple with when they create characters.

For decades, these carefully planned, yet open-ended focus groups have allowed video game companies to probe players’ thoughts and develop and refine new games before the games reached arcades or store shelves. Today, these focus groups provide historians with revealing records that we can use to explore and make sense of the business and culture of gaming.